SF Chronicle – Waymos are getting more assertive. Why the driverless taxis are learning to drive like humans

Editors note: Professor William Riggs of USF is a paid shill of the autonomous vehicle industry. His comments on the benefits of Waymos are as worthy as “four out of five doctors recommend Camel cigarettes” or the even more succinct “More doctors smoke camels”.

See original article by Rachel Swan at the SF Chronicle

Coasting down 11th Avenue in San Francisco’s Sunset District, a Waymo robotaxi eased to a crosswalk, smooth as a spacecraft sticking a moon landing.

A pedestrian confidently stepped into the intersection, barely registering that the car facing him had no one at the wheel. Such self-driving vehicles are ubiquitous on San Francisco roads, recognizable for their high-tech sensors and cameras, as well as their sometimes irritating tendency to follow every traffic rule.

But this Waymo bucked the stereotype.

Before the man had quite finished crossing, the Waymo got to a rolling start. It was one of those subtle driving ticks that humans do all the time, gently letting off the brake so the car crawls forward. Though not generally dangerous, the gesture tends to signify impatience, or a small whiff of entitlement that most humans experience on a subconscious level.

For the Waymo, this sense of urgency appeared new. And the car’s two passengers were mesmerized.

Sitting in the back seat were a Chronicle reporter and University of San Francisco engineering Professor William Riggs, who has established himself as a Waymo whisperer of sorts — a title he sheepishly rebuffs. To advance his research Riggs rides in autonomous vehicles multiple times a week and assiduously studies their performance.

Recently he’s noticed a shift. Waymo’s electric Jaguar SUVs, once known for the rote behavior associated with machine learning, have become more naturalistic and confident. Since launching passenger service in San Francisco a year ago, the vehicles have acclimated to a heavy and diverse mix of traffic: snarled roads, delivery trucks, scooters and cyclists who jockey for space on the road. Within that crowded ecosystem, Waymos now seem less afraid of confrontations. If another driver cuts off a robotaxi these days, the robot might even honk.

“From an evolutionary standpoint, you’re seeing a lot more anticipation and assertiveness from the vehicles,” Riggs told the reporter as their car crested a hill in Noe Valley, the first leg of a rambling journey on a Friday afternoon in May. That day the pair would take three Waymo trips, observing how the cars negotiated sloped streets and busy intersections, weaving around cyclists in the Presidio and making hairy left-hand turns in the Sunset. Throughout these rides, the cars conveyed their human-like qualities in dozens of complex micro-movements. Riggs described these with a term of art: “tentatively evasive” or “minimum risk” maneuvers.

Autonomous vehicles make these tiny, calculated risks whenever they encounter a scenario that would require a lot of eye contact between humans. On Friday, there were many such scenarios. Approaching a construction crew on Diamond Street, the Waymo tacked right, its steering wheel sliding from 2 o’clock to 4 o’clock. When confronted with a wobbly biker near on Lincoln Blvd., the Waymo veered left to give the person a wide berth. At one point, a postal truck hesitated before pulling out in front of the Waymo, forcing the self-driving car to react quickly. For two seconds the Waymo paused to let the truck proceed, exhibiting what Riggs called a “humanistic” response.

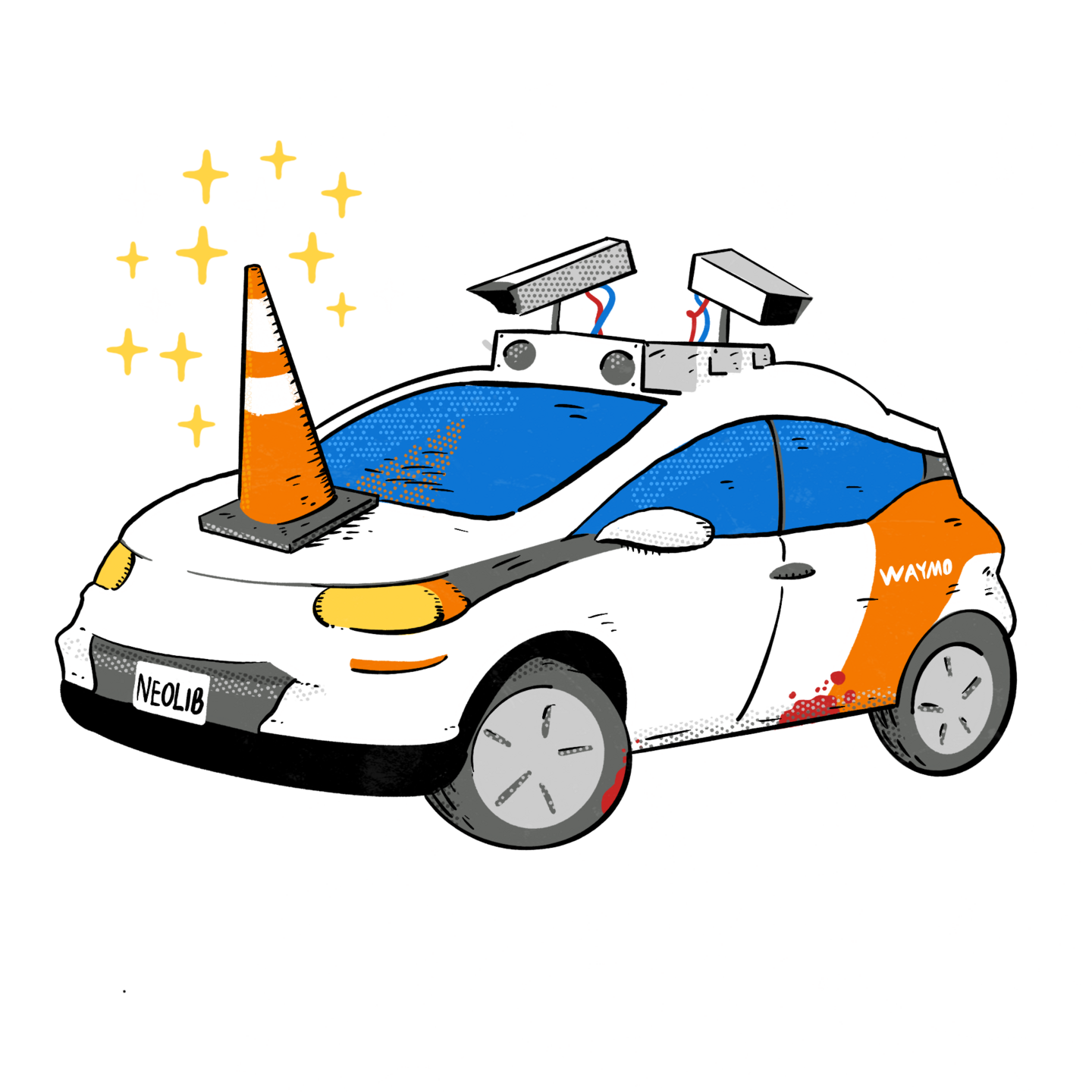

It’s a significant departure from earlier phases, when robotaxis had the demeanor of naive student drivers, and people freely out-maneuvered them. Waymos and other autonomous vehicles wandered into emergency scenes and became confused. They got stuck on wet cement and waylaid by heavy fog. They were easily taunted: Critics placed traffic cones on the vehicles’ hoods, gleefully watching the machines get paralyzed by any perceived obstruction.

Jeering of this nature has abated in San Francisco, where the vehicles now command more respect. WIth the fleet likely driving thousands of miles per week across the city — 16 million miles through December 2024, according to company data — Waymo cars are constantly gathering information about road conditions and fine-tuning their algorithm. Human specialists drive the robot cars to train them, demonstrating how to execute a perfect turn or slow down at the top of a hill.

At the same time, engineers at Waymo have tried to balance their mandate to methodically obey every traffic law with what seemed like a competing goal: to transport passengers in a timely manner.

They were astonished to find that a more brisk and decisive robotaxi was in fact safer, said David Margines, the company’s director of product management.

“We imagined that it might be kind of a trade-off,” Margines told the Chronicle during a video call. “It wasn’t that at all. Being an assertive driver means that you’re more predictable, that you blend into the environment, that you do things that you expect other humans on the road to do.”

To illustrate the transition, Margines presented several videos of Waymos claiming their right of way in chaotic situations. In one instance, a Waymo glides through an intersection on a rainy night in Austin, Texas. To its right, a sedan emerges from behind a truck, plowing into the Waymo’s path. The Waymo rapidly brakes and swerves left to prevent a crash. Then it course-corrects right, tapping its horn. Chastened, the human in the sedan slows and turns down a side street.

“I don’t like to use the word ‘superhuman,’” Margines said. Still, he noted, it would take a “very skilled” human driver to brake that hard while spinning the wheel and honking.

Riggs shared that feeling of enchantment on Friday, marveling at the technology of a Waymo car as it climbed hills in San Francisco’s Diamond Heights neighborhood. Its cameras angled downward, Riggs explained, so it could see over the crown of each hill with more precision than a human eye.

Another expert praised the growth and sophistication of autonomous vehicles but expressed wariness of their new impulse to emulate humans.

“I agree that in one sense, predictability means improved safety,” Matthew Raifman, a transportation safety researcher at UC Berkeley’s Safe Transportation and Research Education Center. Nonetheless, he questioned whether human drivers really set an appropriate bar, given the number of collisions and deaths they cause.

What’s more, Raifman cited the perhaps unsettling “social contagion” of roadway etiquette, manifesting from humans to machines. Human drivers, with their haste, their road rage and their oblivious double-parking, are forcing autonomous vehicles to adapt, Raifman said, in order to accomplish a separate goal: efficiently transporting people to generate revenue.

Makers of autonomous vehicles frequently stress the ways in which their products are superior to people: They don’t drive drunk; they’re never distracted; they’re not texting while driving or overcome by emotions. Waymos have strictly adopted the human traits that make them more dynamic, Margines said.

He touted the fleet’s safety record: According to the company’s own data, Waymo drivers are involved in 81% fewer injury crashes than the average human motorist covering the same distance in San Francisco.

Heading home through Glen Park on Friday, Riggs witnessed just how erratic human motorists can be. A Toyota Tacoma barrelled up the street, lurching into the Waymo’s lane and nearly side-swiping the robotaxi, which deftly veered right. Riggs yelped in surprise.

The incident occurred in a split second, and was forgotten almost as quickly. In this case, the Waymo seemed unflappable. It didn’t honk or stop for an altercation; it slowed down only briefly. The car had revealed its superhuman reflexes, but it still had the placidness of a machine.

See original article by Rachel Swan at the SF Chronicle