SF Chronicle – Why some Bay Area blind people say Waymos are changing their lives

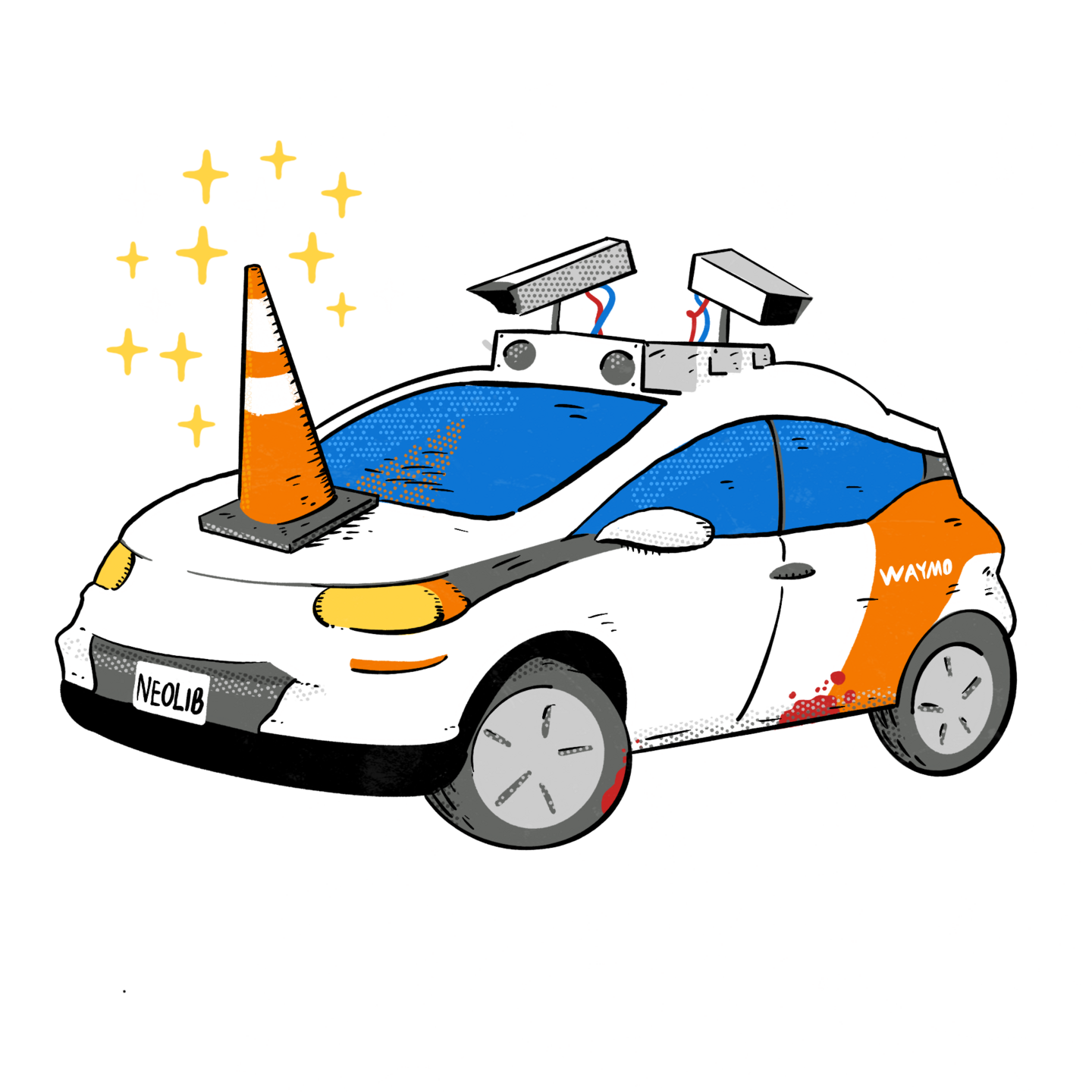

Editors note: it is unfortunate that newspapers publish marketing material from companies such as Waymo. It is also unfortunate that Waymo has co-opted people with disabilities (article1, article2, and article3) by donating significant sums to organizations such as the Lighthouse for the Blind in exchange for articles like this one to be promoted.

The exception is the point the article makes about Uber and Lyft illegally not accommodating people with service animals. This is a very real problem that Waymo has wisely avoided from the beginning, and should be applauded for.

See original article by Maliya Ellis at SF Chronicle

Jerry Kuns, 83, takes public transit as much as he can, but like many San Franciscans, he’ll opt for an Uber or a Lyft if he’s running late.

But for Kuns, who is fully blind, taking a rideshare is like flipping a coin: at least half the time, Kuns says, his Uber or Lyft drivers won’t identify themselves clearly, even though he messages ahead of time asking them to. The car might be sitting across the street for minutes, but he wouldn’t know it.

So increasingly, Kuns turns to a transit option he says is more accessible and makes him feel more independent: Waymo. At the push of a button on the Waymo app, Kuns can honk the robotaxi’s horn or play a melody through its speakers, taking the guesswork out of locating the vehicle, he said.

“I call it ‘my ride, my car,’” Kuns said of the autonomous vehicle company. “I don’t have to interact with anybody, it’s gonna take me basically where I want to go, when I want to go there, and it’s all about my choice and I’m not dependent on your eyes to see what’s around me.”

Kuns is one of the many Bay Area blind or visually impaired people who say they’re increasingly choosing Waymo over traditional rideshare services. While the robotaxis can feel like an unsettling loss of control for some sighted people, many blind riders say the opposite: that Waymos restore a sense of control and agency they thought they’d never experience, or never experience again.

The Mountain View-based company and Alphabet subsidiary, which opened up rides to the public in San Francisco in June and now has nearly 500,000 paid trips a month statewide, has accessibility features that rideshare competitors don’t have.

During the ride, users can opt in to audio cues which describe when the car is stopping at a light or yielding to pedestrians. And after drop-off, the app offers turn-by-turn walking directions to a rider’s exact destination.

Perhaps most importantly, calling a Waymo means certainty that the ride won’t be canceled — a frequent gripe some blind people, especially those who use guide dogs, have with Uber and Lyft.

“I’ll get denial after denial, five or six times,” Sharon Giovinazzo, 55, said of her experience using Uber and Lyft. Giovinazzo, the CEO of San Francisco-based nonprofit Lighthouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired, uses a guide dog, a sticking point with some drivers. “They say, ‘We don’t want a dog in our car.’”

In October, the National Federation of the Blind protested these service denials in front of both rideshare companies’ San Francisco headquarters. “Uber and Lyft provide a service that is of tremendous benefit to blind people, but these companies are failing to address discrimination against us that often leaves us stranded,” federation president Mark Riccobono said in a statement at the time.

Uber’s and Lyft’s policies prohibit drivers from canceling rides because a rider has a disability or travels with a guide dog, and both companies are piloting a feature for people with service animals to disclose their animal when requesting a ride, according to company spokespeople.

“Discrimination of any kind is not tolerated, and our Community Guidelines make this clear,” an Uber spokesperson said in a statement.

“Discrimination has no place in the Lyft community,” a Lyft spokesperson said in a statement.

Waymo has a partnership with Lighthouse and occasionally sponsors events there, Giovinazzo said. Lighthouse was an inaugural member of the Waymo Accessibility Network, a group of disability advocates and nonprofits that has met semi-regularly since 2022 to give the company feedback on accessibility features, according to Rachel Kamen, a spokesperson for Waymo.

For some blind people who lost their sight later in life, they say Waymos give them a taste of a freedom they never thought they’d experience again: the feeling of being alone in a car.

Kevin Chao, 33, who is blind, still remembers the thrill of learning how to drive — before he lost his vision as a teenager. Riding a Waymo, he said, is “just super empowering and liberating,” Chao said. “I was like, ‘This is cool — a blind person in the car without anyone else.’”

Giovinazzo says giving up driving was one of the most difficult consequences of going blind at 31.

See original article by Maliya Ellis at SF Chronicle